POETICA

Critiques

of Poetry and Poetics

Joel Weishaus

Sarah Rosenthal, Editor, A Community Writing Itself.

Dalkey Archive Press: Champaign, IL., 2010

1,

Although my interests presently revolve more around non-locality as displacement, I've been reading a book subtitled, "Conversations with Vanguard Writers of the Bay Area," that canters nostalgically, or at least whose initial signs consist of personal memories. As memories are recombinant, more creative than consistent, "that is how the past exists...The imagination augments, metabolizes, feeding on all it has to feed on, such scraps."(1) Thus, like an old man whose mind wanders in the confluence of past and present, recently I fished from my files a yellowed piece of newsprint, a review I wrote for a San Francisco newspaper during the mid-1960s. Its title is, "Unicorn: Culture is Live Stuff."(2)

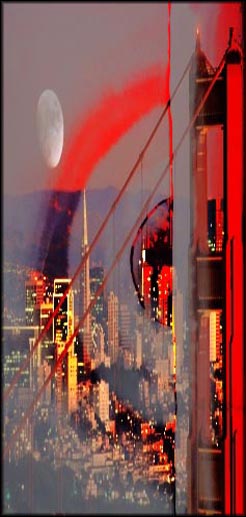

The Blue Unicorn Coffee House, which opened in 1965, was located at 1927 Hayes Street, on the cusp of the Haight-Ashbury District, where its overhead sign bathed "the dank San Francisco night in an eerie blue glow." There, "on Wednesday and Saturday nights amateur and professional poets (the professional being the leaner ones) are invited to recite." It wasn't a laudatory review. I felt that the poetry I was hearing "on the whole is insulated. At its best it strains for freedom; at its worst it drowns in its own quixotic imagery." I was a young writer recently arrived from New York, like so many drawn to the legendary City Lights Bookstore, the Beat Poets, and blankets of mystical fog rolling in to haunt San Francisco's sunny Mediterranean disposition.

As I reflect on this book, built around interviews with distinguished poets who worked, or still work, in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, I recall the visions of "an intelligent American woman of the introverted intuitive type," on which the psychologist C.G. Jung held a seminar, As Jung told it, at one point, when she saw "the white city from the distance, she naturally thought, as anybody would, 'There is the place of rest, the place of completion, the real goal.' But the Vision said, 'By no means.'" "Well," Jung continued, "that is often the case."(3)

2.

How to discuss a collection of interviews; in addition, one of writers living within a place that itself has many avenues and disparate climates, a community. What's called a community of poets is usually those living in the same city, or region, who read their poems, mainly to each other. Near the end of her illuminating introduction to the history of experimental poetry in the Bay Area, Sarah Rosenthal writes that she chose twelve poets "in part because in an utterly naïve way I imagined that the project would take me a year (an interview per month!)—but twelve, too, because I felt that number would allow me to include a range of poetics within the Bay Area experimental community." Instead of one year, her project took nine years to complete, which explains her ease with each poet's oeuvre. One feels secure not only by her knowledge, but also her respect for the interviewee, along with the enthusiasm she sustained over nearly a decade of research and writing—all of which makes the ripostes a pleasure to read. But why these twelve poets in particular? Are they the ones with the brightest auras, a "particular power which an image or object has by virtue of its singularity, authenticity, and 'embeddedness in the fabric of tradition.'"?(4) For me, this raises the problem of how to do justice to all twelve, not having one outshine the other. No, I cannot go this way.

3.

"In every reclamation of the past," wrote Michael Murphy in his novel of extraordinary psycho-biological effects, "there is a new freedom to open the future."(5) One day in 1970, I climbed the steps in City Lights Bookstore to the small office of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, editor and poet, whose A Coney Island of the Mind was legendary among my friends in New York. I had collected a manuscript of poems generously given to me by writers who lived in Bolinas, that small town just north of San Francisco where poets from around the country, some of them celebrities in the field, had settled, or were in extended residence. The name of the manuscript I offered was The Bolinas Poets. "I don't publish books from particular places," Ferlinghetti said. Quickly recovering, I replied, "I also have another title in mind, On the Mesa. "If that's the title," he said, "I'll publish it."(6) How our vision of the world has changed, or should have changed! In response to technologies for communication and distribution that weren't available until recently, definitions of place, as elucidated by Western philosophers, beginning with Plato's friend, Archytas, are constantly under revision. (7) So that now we are able to envision non-places, along with the betweenness of various places.

Returning, for a moment, to the last century. In organizing On the Mesa, to which fourteen writers and two visual artists who were then living in Bolinas were invited, I decided to place Joanne Kyger's poems near the center. This allowed the only woman poet of stature living there at the time to give the book the cohesion of a community [In response to a question from Sarah Rosenthal on the present writing community in Bolinas, Stephen Ratcliffe said, "I do participate in a little poetry community in Bolinas, but it consists more or less of Bob Greiner, and Joanne (Kyger), and her husband Donald and me. We get together for dinner and we read things."(p. 221)], especially as her first poem is about the wedding of another of the anthology's poets. (8) Alternatively, Rosenthal's solution was to list the contributors to her book alphabetically, with an evocative rubric below each interviewee's name. (9)

4.

In a recent conversation with New Media critic Edward Picot, with reference to Poetica I said, "My primary interest is in reviewing books of poetry in which the genre is used to expand and deepen other fields."(10) When I said this, I had the sciences in mind: how poets may draw metonymical lines through pages of apparent facts, where physical theory may veer into phonetic art, equations morph into metaphors, the goggled eyes of marine biologists open further to become wide-eyed readers of poems that may also broaden the brims of archaeologists to excavate a deeper humanity than just the shards of bones and middens can tell. Here, as usual, how poetry influences other arts is what surfaces. (11)

To what extent does a community of writers, like the departments in which many of them teach, present a danger of not venturing far from shared didactical roots? I suggest this old point is worth resharpening, as "would-be artists today don’t need to haunt the Moulin Rouge or Cedar Tavern to rub shoulders with today’s Picassos and Pollocks, with a computer and modem they can tap into a vast network of shared resources and ideas online.”(12) Indeed, with internet-based communities in which friends and colleagues can communicate through distant servers, the notion of place-based communities may be already outpaced. As someone with fond memories of meeting friends and mentors in North Beach and other coffeehouses, I bemoan the thought that future artists may not have such intimate exchanges. However, the surge of international and interdisciplinary activities we are experiencing because of the internet may be worth the loss of smelling someone else's coffee and hearing the same music.

5.

Nathaniel Mackey's long affair with music, especially Jazz, of which, he wrote elsewhere, "frequently and characteristically aspires to the condition of speech, reflecting critically, it seems, upon the limits of the sayable...,"(13) ripens within the discourse of poetics. Rosenthal says to Mackey, "Reading your work resembles, in certain ways, listening to someone like (John) Coltrane. Like him and other jazz artists, you seem to be listening to idea and sounds and riffing on them, massaging them, inverting, spinning, braiding, and fraying them." Mackey replies that he's "a slow improviser write in spurts, through a combination of pressure and relaxation."(p.148) Here's an example:

I wake up mumbling, "I'm

not at the music's

mercy," think damned

if I'm not, but

keep the thought

to myself. (14)The way I hear this poem (they are not addressing it, in particular), the music is in the spaces, especially the obvious long beat, then thump, between "mercy" and "think damned." Mackey addresses this "state of in-betweeness," this "non-place...that's been at the root of all my involvement with music..." While "the sound itself, we know, is physical." (p.149)

This takes us to vibrational energies discussed in the Vedic texts of ancient India, the physical power of mantras, and the focused sound with which advanced martial artists are able to stop an aggressor. There is also unfocused sound, "a sphere without fixed boundaries, space made by the thing itself, not space containing the thing."(15) Nathaniel Mackey, a Professor of Literature at U.C. Santa Cruz, is an important teacher, along with poet and novelist, whose books, Chris Funkhauser wrote, "are maps of a large region. In them, he transverses grounds of literal and figurative forests, fields, and sands he knows well." (16) However, many of these interviews seem too sure-footed, navigating around muddy puddles, avoiding slippage, especially when their own work is being discussed.

Robert Bly told a story about hearing a reading in London by the late Robert Creeley. "He proceeds from word to word," Bly said, "not only with tremendous uncertainty, but also with a kind of anguish which is perfectly apparent in his voice and manner as he moves from one word to another."(17) It is not Creeley's anguish that interests me, but his uncertainty. Even though he ended his career as a distinguished professor at SUNY Buffalo, when we trace the erratic course of his life, it doesn't describe the familiar trajectory of kindergarten to tenure.

Bly also says that (in the 1960s), unlike the English poets the Americans were not there to entertain. Obviously, he wasn't talking about the Beats, who were still on the scene, and whose stagecraft was even admired by a young Bob Dylan. (18) What still fascinates me about the Beats is not only that they were last American poets by whom the mass media felt threatened enough to mock, but that most of them didn't pursue an academic career, at least not until later in life. Instead, besides traveling extensively, they took jobs that gave their poems a ring of working class authenticity. This is not to say that the writers gathered in this book don't have a larger life than their scholastic rounds. Rather that, presently, most American poets recognized by critics and publishers are specialists, with whose work experience, primarily in academia, the general public doesn't identify, opening space into which non-academic expressions, such as open mic, rap and slam rush.

6.

In "Placing Silence," the interview with Kathleen Fraser that begins A Community Writing Itself, Fraser reminisces about a summer she spent in Italy, at a time when she and her husband "couldn't yet speak Italian very well." Sitting on the periphery of a group of woman, she smiled and felt "painfully outside" their conversation. "Since I couldn't say much, I took notes on what I noticed and thought I was hearing: In every direction I looked, there was an incredible visual treat of food, bodies, trees, birds, and water." This "deficit" in words "thrust me into the witness position," giving her "an entirely new and visually privileged subject matter and it shaped the disjunct quality of the serial poem that I began to write out of—down to the very placing of the phrases," (p.48) She found her poetic voice and style in the aphasia of separateness.

Tight fist that held you,

you entirely separate — (19)In this same collection of poems are Fraser's "Etruscan Pages." She tells Rosenthal: "I'd visited a number of largely untraveled Etruscan ruins and was quite taken by the beautiful Etruscan alphabet carved into tombstones recovered in several museums. I wanted to presence (sic) the letters I saw there, originally scratched into tufa (volcanic rocks used for burial stones) with red berry juice, as well as those letters pressed into very thin gold tablet or 'page' that now hangs in the Villa Giulia, the Etruscan museum in Rome." (p.58)

The letter A is a plow

(mare pulling into mare)

horse plowing sea

MaremmaWas A

where

you made and

unmade your mind... (21)First I am reminded that Poseidon (Neptune) is both the god of horses and the sea. Then one day, from a newly ploughed furrow in a field near the river Marta, in Etruria, a divine child — Tages, grandson of Zeus — suddenly arose. To a gathering of astonished priests, the child chanted a sacred doctrine, which they wrote down. Then the child disappeared back into the earth. "Absence," wrote Jacques Derrida, "as the breath of the letter, for the letter lives." (20) Derrida is writing about the work of the late French poet, Edmund Jabès. In Rosenthal's interview with Michael Palmer, "The Recovery of Language," Palmer speaks of when, in 1983, Jabès and his wife, Arlette, stayed with the Palmers. "He talked about respiration in the work," the American poet said. "I said to him at one point, One of my problems is that I keep trying to go deep into it, yet I keep bobbing up to the surface. He said, If you stay under, you'll drown." (p.171)

It was around this time that Palmer was writing a poem which includes the lines:

A was the face of the letter

reflected in the water below. (22)In Jorge Luis Borges short story, "The Aleph," the writer is invited into a cellar to see an Aleph, a point which he is told contains all of time and space from every "point and angle." "And in the Aleph," Borges continues,

I saw the earth and in the earth the Aleph and in the Aleph the earth; I saw my own face and my own bowels; I saw your face; and I felt dizzy and wept, for my eyes had seen that secret and conjectured object whose name is common to all men but which no man has looked upon—the unimaginable universe." (23)

Seeing the Aleph began Borges says, his “despair as a writer,” because language is a set of symbols that derive from a shared past. Thus, how could one speak of something that encompasses all experience in a single point? Borges also points out that aleph is "the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet...For the Kabbala, the letter stands for the En Soph, the pure and boundless godhead; it is also said that it takes the shape of a man pointing to both heaven and earth, in order to show that the lower world is the map and mirror of the higher." As in the Hermetic saying, "As above, so below."

Elizabeth Robinson, in an interview aptly titled, "Falling is the Safest Thing to Do," when asked about the words "fall" and "gravity," she replied that she thinks of them "in terms of the precariousness of existence." To which she adds that, "Poetry works for me at times as a wedge against the sense of complete endangerment, a psychic and political precariousness." On a biographical note: "I grew up within a very dualistic atmosphere. Like many Protestants, I was taught to be ambivalent about my own embodied experience and about sexuality. Then I made the great discovery that bodies are rich and in some ways always beyond their own limits; that it is good to be a body." (p.236)

Like televangelists, too many American poets tell us what we already know, perhaps to justify why, besides helping their teaching career, they publish poems in a country whose residents are for the most part ignorant of literature, and it is getting worse. So the poets muck around in their own head, drowning in the pleasure of their ectoplasmic voices.

But the ghost beguiles and I cannot resist putting my hands in,

wrist-deep, pulling apart where I reach, finally, the streamof the original,

the prime number, the place where parting cannot occur. (24)7.

Where should I go from here? To another interview? As opposed to a review, a critique forces the critic to grapple with his own self. The more honest he is, the more he places himself in danger. It is all psychological, the mind's logic which, unlike the brain, doesn't compute. Nothing mindful adds up, no equations balance; there are no prime numbers, no foundation, no security, no singular almighty God. Delirious with this knowledge, this gnosis, I dance in the dusk of a warm summer's eve, kicking up dust beneath my feet, before the earth opens for me.

References and Notes:

1- Kenner, H. (1971) The Pound Era. Berkeley: The University of California Press.

2- My tearsheet has no date or provenance.

3- Jung, C.G. (1964) "The Interpretation of Visions: V. Excerpts From the Notes of Mary Foote." (Spring Journal)

4- Gilloch, G. (2002) Walter Benjamin: Critical Constellations. Cambridge: Polity Press.

5- Murphy, M. (1988) Jacob Atabet. Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

6- Weishaus, J. (1971) Editor, On The Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writing. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

7- Jammer, M. (1964) Cited in J.J. Smart, Problems of Space and Time. New York: Macmillan.

8- Kyger, J. "A Testimony for Ebbe and Angela on their Wedding, November 29, 1970."

9- Poets interviewed are: Kathleen Fraser, Robert Glück, Barbara Guest, Brenda Hillman, Nathaniel Mackey, Michael Palmer, Stephen Ratcliffe, Elizabeth Robinson, Camille Roy, Leslie Scalapino, Juliana Spahr, Truong Tran.

10- "The Gateless Gate-An Interview with Joel Weishaus" Rain Taxi. http://www.raintaxi.com/online/2010summer/weishaus.shtml

11- I have in mind the Critical Arts Ensemble, and especially the hellish experience one of its members, Steve Kurtz, lived through when persecuted by the FBI. Not so much because Kurtz was an artist and political activist, but that he used his knowledge of biology to make his art. See, Strange Culture. New Video Group, DVD, 2007.

12- Blais, J & Ippolito, J. (2006) At The Edge of Art. New York: Thames & Hudson.

13- Lang, A. & Mackey, N. (1993) Editors, Moment's Notice: Jazz in Poetry & Prose. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press.

14- Mackey, N. From, "Capricorn Rising."

15- Carpenter, E. & McLuhan, M. (1966) "Acoustic Space." In, E. Carpenter and M. McLuhan, Editors, Explorations in Communication. Boston: Beacon Press.

16- Funkhouser, C. (1994) "Chris Funkhouser On Nathaniel Mackey's Recent Work." RIF/T (Winter) http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/authors/mackey/review1

17- Bly, R. (1984) "On Unfinished Poets: An Interview with Scott Chisholm (July 1969)." In, Talking All Morning. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

18- Wilentz, S. (2010) "Bob Dylan, the Beat Generation, and Allen Ginsberg’s America." The New Yorker (August 21.) www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2010/08/sean-wilentz-bob-dylan-in-america.html

19- Fraser, K. (1993) From, "Frammenti Romani:" In, When New Time Folds Up. Minneapolis: Chax Press.

20- Derrida, J. (1978) Edmund Jabès and the Question of the Book." In, Writing and Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

21- Fraser, Ibid. From, "Norchia."

22- Palmer, M. From, "Seven Forbidden Words."

23- Borges, J.L. (1970) The Aleph and Other Stories. New York: E.P. Dutton.

24- Robinson, E. From, "Congratulations."