SILVER LINING

Review of Silver Lining: Photographs by Anne Noggle. The University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

1.

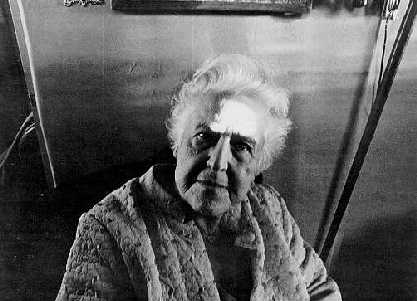

The first picture in Anne Noggle's book, Silver lining, is of her mother, Agnes. The background seems to want to embrace the woman looking into the camera, who seems unaware of a large patch of light, a poultice, on her forehead, aware only of the camera. Swathes of light and circles of night, the artist would use these until confident of where symbols fall away and the world itself becomes symbolic.

2.

At age thirty-eight Anne Noggle was a freshman at the University of New Mexico, majoring in Art History. Before that, she had been a pilot and flight instructor in the Women's Air Force, serving during World War II. After the war, she taught flying, did stunt flying, and dusted crops in the Southwest. Noggle recalls that "The statistics were that the average crop-duster pilot had a life-span of about a year and a half. You lived on a high that danger bestows on you. Only now counted."

One limitation of the traditional photograph is that it is a picture of something, separating the viewer from the original object by both time and space. When the picture was taken our seeing it was only a remote possibility, so to accept its validity we must accept it at face value. Not what it images, but what it is. Thus photographs, as art, are not from the past, but emulsions of objective formulations recognizable in the present, successfully projected into the past. Painting and photography are here different only with respect to materials used. That is, like a painting, a photograph accepted as art must not be viewed as an image from the past projected forward (as with snapshots), but of the present.

Snapshots have their own virtues (as do crafts), one of which John A. Kouwenhoven points out as being the ability to teach us "to see things not even their makers had noticed or been interested in." But their raison d'etre lies in documentation, telling "the truth of a single instant."

It could be argued that we never experience Art, which is Reality, because Reality operates outside of time, while nervous systems are time-bound. We can only experience the past, be it a micro-second old. In effect, I am my own ancestor. And looking at old pictures of "my" image is confirmation. It is intent, in this case, that makes a work of art. And faith.

3.

From crop-duster to active duty, again, with the Air Force, Noggle found herself, literally found herself, in Paris, in the Louve--returning again and again to the paintings. Then, because of emphysema, she received an early retirement and moved to New Mexico, where her mother and older sister had settled.

In his foreword to Silver Lining, Van Deren Coke recalls:

I first encountered Anne Noggle encountered is the right term, for the word meet does not accurately convey the essence of the experience) when I was chairman of the Department of Art at the University of New Mexico....She affected a kind of tough-guy stance, but since she was about my own age I was able to see her as a delightful individual who had firm ideas and a strong vocabulary to express them.

After she completed her undergraduate degree, Coke felt Noggle "had the makings of an insightful art historian;" but she had discovered Photography. "It was the first time since I'd been grounded that I felt the same excitement that flying always gave me."

One of the advantages of living in New Mexico--being isolated, and insulated, from the mainstream Art World--is the opportunity to develop your own vision and toughen it, before being subjected to the blows of the critical establishment. Thus, even though at the time Noggle came to photography portraiture was out of favor, she sensed, and acted on, that all truths are feelings; and, as I.B. Singer wrote, "Feelings put on bodies, are themselves bodies."

4.

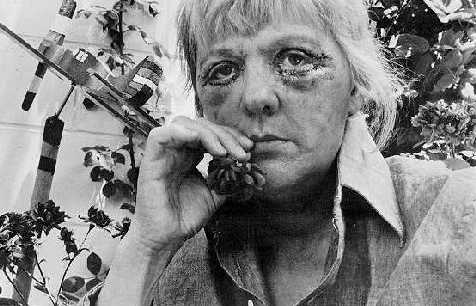

In 1975, shortly after having face-lift surgery, Noggle made a series of self-portraits.

In No.3, her face is still swollen, flesh beneath

the eyes discolored as if she just came out of a fight--the loser.

Yet victoriously she holds a

flower to her lips.

Here is where the artist enters into her art, not only identifying with aging

women, while

playing with its possibilities, as only an artist can. "If I am shown in

my face-lift as attempting to stave off the visible aging process, it is also

an indication of what an

exercise in futility that is."

The print translates back into its native language, different of course, hardly recognizable, yet its flavor evokes the original. It is our language again, not the photographer's, not the scholar's, it belongs to us all, a treasure claimed by our eyes. Photography is a struggle to make intimate contact without direct involvement. It is a shy, one-eyed art. But Noggle isn't shy, and both her eyes are wide open. She turns the camera around in a kind of schizophrenic journey into herself: a double image of persona and soul reflecting each other ad infinitum. It is not the flesh that is lifted (this being camouflage, a mask) but the soul that is plumbed--lift having to do with puer, Spirit, Child.

Though she is flying again--the artist cradling the Child--it is downward, inward. In AA Speech Delivered to the Class of 1983, Portland School of Art, Maine, Noggle related this experience:

...I was in this plane in World War II and intentionally spun it. It was way out of rig and wouldn't stop spinning, and I tried to get out and found the centrifugal force too strong to even move so I decided that if I were going to die, I would die trying and than I did everything they had told us not to do with the controls and the plane came out of the spin...

The material world exists only in order to demonstrate its limitations. This is what Noggle's photographs seem to be saying. I am my own history, an accumulation of experience from the beginning of this universe to the moment of my death. And with death, myth arrives, the photographs fade but don't disappear.

The photograph exposes "the truth of the lineage" (R. Barthes); not that I existed, but that we exist. Psychologist Robert Jay Lifton says of the aged that "They wish specifically to reassert elements of their individual lives that can connect with the lives of all others." So that beside being one's own history, each of us is a holograph of the entire history of the species. This is a fact we seem to have to prove to ourselves again and again during various stages of development. The need for connection may be what's behind Diane Arbus' freaks: to be "taken in" by the eyes of more acceptably formed people. Children, adolescents, the dying, and the deformed--outcasts, each in their own way, all craving for membership in the tribe.

The artist, however, must stand alone. How many times has this been stressed? Janice Zita Grover, in her introduction to Silver Lining, gives this Rikean reminder:

The artist's life, whatever the medium, whatever the accomplishment, never becomes easier on a day-to-day basis. While the odds of more frequent or continued success may increase, there's little comfort in this knowledge: the possibility of failure right now, this time, seems as great as ever. To cut off comforting everyday contacts, the sort of human transactions that are prompted by unqualified affection rather than superior performance, to voluntarily court opportunities for seeing how signally one can fail, to close one's life into an intense solitude requires great discipline and courage.

5.

One cannot enter into a state of solitude, and survive, without a wild sense of humor. Although Noggle can "pull faces"(for example, in Myself as a Guggenheim Follow), and in fact she seems always to be laughing at, taunting, daring the camera, saying "You have no power over me," real humor is subtle and crafty. I see this in Stonehenge decoded.

Here the artist poses her belly, pubis, and upper thigh, which loom to the side of a vast desert landscape and turbulent sky. Unlike Paul Caponigro's pictures of the Stonehenge menhirs, here is living flesh. Flesh venated and runneled, as the land is not soft rolling hills, but sand, saltbush, snakeweed, distant mesas and portentous clouds. A monument runic as any ancient stones; erotic too, with a hint of clothes above the navel. Because we are vulnerable; not petrified, not fossiliferous, not hauled and lifted into place. Noggle is open to soft ambient light; comfortable, yet absurd in her corner of the desert. She speaks for the flesh that moved the stones into place, fertility of imagination, and, used to measure the phases of time, this woman who is time and rhythm. What stone has more knowledge of cycles than a woman?

The humor of Stonehenge Decoded is, for me, that we search for secrets in old glyphs, instead of in the mystery of our own falling, and failing, flesh. All the hypocrisy of religion, of "heaven above," is evident in this picture. "Just this!" as the Zen Master points.

6.

We can no longer accept a work of art on its own. Walk into a gallery, or look through a book of photographs, with feet to floor, to sediment below, to Earth's hot core radiating out...it's all referential. "There is a place within," noted Caponigro. "That is constantly alive to how this whole structure is put together."

The place within the eyes of Agnes,

Noggle's aged mother lit against the Void that would engulf her.

Eyes appear

in many guises, and

from many directions. "The Greeks," Barthes tells us, "entered

into Death

backward: what they had before them was their past."

There are eyes that cry into themselves, as in Rose Wiley, Seamstress, lost

to a purblind digital technique, or the luna eyes of Yolanda in Her Silk Hat.

And, of course, the eyes of the artist herself, incarnating with every picture

taken Minor White's benediction:

Out of my love for you,

I will give you back to yourself.

7.

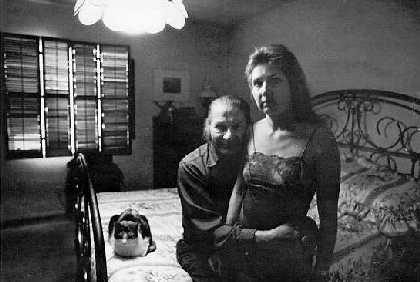

Of the "Silver Lining" series of portraits of married couples from 1979, five are in this book--men and women who have lived together, yet apart, for a long time.

At some early point in gestation, the genetic code releases

information: straight ahead to female, or secrete the necessary hormones

in order to make a male. The balances vary, complicated by later social

conformations. What is a woman? What is a man? How should we relate

to each other, and to ourselves?

"The field is the only reality," Albert Einstein said. The desperation

of lovers to meld into one is telling. That struggle, beginning with Adam and

Eve, beginning with

Knowledge (Gnosis), is the "'poison' of

understanding," as C.G. Jung named this snake.

In Silver Lining No.1, man holds woman unconvincingly. How many times have they struggled to unite on this bed? The best they could do, the best anyone can do, is hold onto each other. And the cat wants affection too.

The wary look of the wife, and her smiling husband behind her, light this irony. "I do not paint things," said Matisse, "only the differences between them." What the physicist calls the "probabilities of interconnections."The photograph, a mirror, like the mind of an enlightened being, reflects its viewer. What we see is what we get. The positive print is of the underside, the negative of the object printed. "I love the enigma of it all," says Noggle. From the beginning, the Two in the One has been our burden. We enter, or are entered, as gods...and withdraw exhausted as humans. To come is to go.

Silver Lining No.5 shows wife leaning into husband. His dark suit and her dark dress form a continuum. Her smiling face rests on his shoulder like an apple ripening while rotting. Behind them are photographs of her as a young woman, with their child. All here together, the same age, only looking younger, the same time, which is my time as I look at them, time being "nature's way of keeping everything from happening at once." (Susan Farley).

In all these portraits, in all portraits, all faces, smiling or not, is the knowledge of "the suddenness with which terror can strike." For Noggle this means "that I will wake up and find I have become a completely rational being, with a finite set of values, within whose framework I must find my manners and dream my dreams." This series of pictures, Grover informs us, "hangs in (Noggle's) home like a gallery of timeless reflections on a road-not-taken by the photographer herself."

8.

In 1982 there was a series of photographs from Seattle, and the next year from Texas. Other pictures include another of Yolanda (there are several), this time wearing a fur hat, with a luminous eye on the lighted side of her face, the other side dark as with us all. And a portrait of landscape historian J.B. Jackson in motorcycle jacket.

Lastly in this book is The Late Great Me. Her face veiled, after having been exposed for so long, eyes half-closed, she mourns herself, with lips smiling around their corners. There is an Hasidic maxim that says one should have two pockets. In the right pocket must be the words, "For my sake was the world created." And in the left, AI am but ashes and dust."

(c) Joel Weishaus 1994

(c) Artspace 1984