MARKS IN PLACE

Review of Marks in Place: Contemporary Responses to Rock Art. University of New Mexico Press. Albuquerque, 1988.

l.

A rock poised in the wilderness, eroding away over millennia. On the rock's pitted face are human marks--incised, pecked, scratched, carved or painted. On every continent except Antarctica we can find examples of these primitive petroglyphs, pictographs, and geoglyphs--evidence of our need to objectify vision, along with the more mundane chores, such as keeping track of the seasons, of sacred days, identifying tribal territory, or tracing magical signs for attracting and glorifying quarry; then, maybe just to doodle.

In this century, particularly in France and Spain, caves have been discovered whose walls are a gallery of paintings dating back more than 25,000 years. What is amazing is that, in the words of anthropologist Alexander Marshack, "what seems to be emerging...is a view of early man's way of thinking as being exceedingly complex and surprisingly modern." Max Raphael: "We see that despite external differences, these works of art are fundamentally the same as those of today." We are born old, to which we must add something new.

"The oldest rock in North America," Polly Schaafsma states, "was made by small bands of hunter-gatherers who occupied (North America) for several thousand years." This work has been continued ever since, each glyph a palimpsest of the larger story of human communicative endeavor.

As what we call meaning can only be understood within each cultural frame, and these cultures are long extinct, the photographers who participated in the Marks in Place project wisely searched for hypostatic gestures, the "primordial attunement of one human existent to another out of which all language comes." (Walter J. Ong)

Philosopher Paul Wienpaul, while staying at a Japanese Zen Buddhist monastery, wrote in his diary, "I felt strongly for the hundred generations, how I am a product of them." Considering contemporary art's political, psychoanalytical and linguistic interests, the search for the past may be, especially in the case of Native American art, "a kind of exorcism," as Lucy Lippard suggests. "The victors' heirs return to the sites because in some ways the voices of the vanquished are more eloquent than the voices that eclipsed them." Or is it simply the fact that before our modern world could come into existence, marks such as these had to be made?

Not an exorcism, then, but a recovery. Not guilt, but questioning within the sweep for our mythological home, on whose foundations we built the fantasy we call history.

2.

So unassuming is this rock, that if it wasn't for the glyphs on it pictures of it would not have been taken. In turn, it is the discourse of photography that raises these marks to "art," becoming remarks and remarkable, as "the photographic paradox lies in the need for translation alongside translation's redundancy." (Frank Webster)

At a spot in the Arizona desert named Sears Point, there is a rock split through its center. I believe this, yet all I have as evidence is a black-and-white two-dimensional picture. In situ, the rock may have already disappeared to weathering, vandalism, or insatiable land development...but this no longer matters, as our artists are preparing us for future absences: with the supplement that "replaces nature and so becomes an integral part of it, to the point in fact where the artificial and the natural become inseparable, one and the same. Nature, in all its plenitude, appears in its real form, that of myth only." (Josue V. Harari)

The picture's grisaille tones reproduce the feeling of the desert while losing its sensations. It works internally, with gradient moods on a somber scale, while the glare, palpations of heat, the fear of reptilian poisons, the constant ache for easily replenished moisture, all fade into shades of resolution. In this silence, incidentals are magnified. Even as it leans back on a companion for support, its planars constantly shifting, exposing a mosaic of forces, the rock, which first drew human attention eons ago, is still hugely important to our orientation.

"When I photograph," writes Linda Connor, "I try to organize the image to best describe (the) shape of spirit. Sometimes I will do this by using symmetry or by collapsing space and scale." There is a modernist sense of flatness here, fading mountains balanced on the rock's head, a sky the color of dead trees. What is far appears not too distant; time collapses too. "My aim is to photograph in a way that denies time and our social context by avoiding cultural clues," Connor further states. "Progress and history interest me less that the eloquence of human imagination as it flows from all time, Paleolithic to the present."

All symbols contain "cultural clues," so this project appears naive. But it is probably purposefully so. Indeed imagination is humanity's most enduring and eloquent prayer.

At Nazca, Peru, Connor found a wall painted with luring shamanic figures, their power in the hoist of armless shoulders, and the evenness of their chiaroscuro, like ironed shrouds. While on a side of Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, fingers sign in negative prints made probably by blowing pigment through reeds.

Henri Breuil suggests that "hand prints were probably the first wall paintings." Jo Anne Van Tilburg attributes their recognition to an accident. "A sweaty and dirt-stained palm upon a rock wall may have struck someone's fancy in some way." And Max Raphael felt that "the hand was the organ that enabled man's spiritual and physical forces to strive outward, that in the struggle for existence secured his life against animals and his power over other men..."

"Hand prints stamped in paint at places identified as sacred may have been left in order to identify the bearer of a prayer request," writes Polly Schaafsma, "or they may have been left as a means of obtaining some of the power residing at the spot."

Andre Leroi-Gourham advanced the theory that certain hand prints on Paleolithic cave walls represent "the play of fingers as a silent signaling of the presence of game of one sort or another." Finally, here, R.B. Onians reminds us of how to the Hebrews the human hand represented the "procreative life-soul," and of how Jesus and his apostles "by 'laying on of hands' transmitted the spirit." "In early Christian art," Onians continues, "God the Father, or perhaps rather his 'Spirit,' is often represented by just a hand."

Or was the hand simply the easiest physical mark to make in order to say and to record "I AM"? What could be more natural than to appropriate one's hand--maker of tools, weapons, love--for a symbol of one's existence?

3.

For Rick Dingus, Canyonlands, Utah, is a site for hand prints like schools of fish petrified on the wet walls of the mind, as in his Handprints in a Cave, hands stylized with circulating energy, to which Dingus adds his own hands by sketching randomly on the photographic print.

Dingus writes that his "photo-drawings are like magical fetishes that are as much the product of inner states as they are of external circumstances." His is a ritualistic world of interactions of which, Novalis says, "every line is the axis of a world." Dingus's Interior: Cave Kiva in Northern New Mexico (Mythical Fragments) is a physicist's cloud chamber, in which subatomic particles crash and form new images within an oneiric paradigm. The photographer literally draws the glyphs out of their original frame, extending rather than inhibiting the dance of their myth.

In Displaced References, Canyonlands, Utah, pictorial planes are shifted as if they are continental tectonic plates, riding and colliding. While art critic Lucy Lippard complains that "we are offered slipping glances of each site, glimpses which contradictorily focus on static single images: one glyph, one place...," psychologist Peter Bishop counsels that "fragments also heal."

Irony: Ancient artists would not be able to recognize their work reproduced in these discrete two-dimensional rectangles of coated paper. "Such an inability," speculates Allan Sekula, commenting on the reported inability of a Bush woman to recognize her son in a photograph, "would seem to be the logical outcome of living in a culture that is unconcerned with the two-dimensional analogue mapping of three-dimensional 'real' space, a culture without a realist compulsion."

Bush people live in Southern Africa, in a region that has "the richest treasury of (parietal) Stone Age art in the world." (R.T. Johnson-Major) But a photograph, unlike a rock painting "floats." Bush people, being nomadic, orient themselves by specific sites during specific seasons, while the photograph, at least as it was presented--e.g., in hands not placed. In addition, the photograph shown to the Bush woman was probably black-and-white, thus, again, non-referential to her actual world. In other words, what a picture of the desert, for example, leaves out is the desert itself, its availability to the whole sensorium. This act of substitution is Photography's disposition and its admonishment.

I suspect, however, that rock artists, after learning how to read the "code," would admire Rick Dingus's darkroom visions with their hand-drawn phosphenes ("varied geometric patterns that appear in the visual field when no visual stimuli are entering through the eyes...the initial stages of hallucinary experience" [Ken Hedges]). As Polly Schaafsma informs us, "Rock art at vision quest sites may be influenced by drug-induced visions and (may) be less conventional in its symbolism."

Art is the in-between, the ever-apart, the mooning for the symbolic that does not conform to signification.

In Fitch's Fire, Northern New Mexico, Dingus pays tribute to fellow artist Steve Fitch. A fire blazes. The 8-by-10 camera, set on its tripod, is poised to record. On a wall, a spermatozoic glyph meanders with the photographer's silver saltations. What we see is the world seen before the world we see. We don't see a picture, but picture of a picture, whose fire burns color into our eyes.

4.

At night, in Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, a wedge of flame points to shamanic figures reminiscent of those found at Nazca, Peru--some of the same robed, armless revenants; but these are smaller, thinner, and scaled as if in perspective, a sort of Giacomettian council of old souls.

Steve Fitch is an artist of singular places which interact with the landscape they inhabit. His camera practices a sort of feng shu. For him, the viewer and the viewed are all part of a greater system. "A place," says Fitch, "exists within the flow of time-- past, present, future--and within the flow of space as well, so that near and far are part of a continuum. A place is identifiable but, unlike a site, not separate from its surroundings." So here he chooses Shamanlike figures in Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, where ghostly figures stand around their master, waiting to be guided back into the bowels of the rock.

Why here? What could have prompted an artist to sit down here and do this? "The discipline of imagination," psychologist James Hillman writes, "asks 'where'--where to place this happening; and by asking 'where' and fantasizing in terms of place, the psyche enlarges its interiority, and the space by which it carries meaning." No matter how vast the space, we are only always inside ourselves, making faces.

In Night on top of Comanche Gap in New Mexico, spots of mottled lichens share the rocks with childlike drawings of goblins, birds, and eclipse of the moon, a star, a man holding a branch. Place is more important than "the ultimate clarity of the figures," Steve Fitch explains; adding:

Rock art, really, is a metaphor of connectedness. It was created by people who were, of necessity. an intimate part of their environment, their place on earth, and it continues today as a kind of message that communicates that intimacy.

Habitation, however, has never been endemic to the Euro-American ethos, ironic in view of its strong defense of personal property. The American myth is one of exploration and exploitation, an impulse which drew many of the great 19th century expeditionary photographers west. This is an insistent restlessness that carries into the present its relentless search for frontiers to conquer.

With landscape photographers comes the urge to ask where the picture was taken, as if we must constantly orient ourselves on this planet that mysteriously is still so foreign to us. We can accept pictures of people as a general category, but unfamiliar landscape seems to trigger agoraphobia, a fear of guideposts disappearing, of not being able to find the way home.

One way Fitch establishes a site is to strike a beacon fire. While a small, controlled burn reassures us, even as it adumbrates and ensorcells, fire is also an instrument of transmutation. Thus Mircea Eliade points out that "the incombustibility of the shamans proclaims that they have gone beyond the human conditions, that they have something of the condition of 'spirits,'" flickering on walls and fading into night.

5.

During the 1960s, Polly and Curtis Schaafsma surveyed and photographed rock art sites scheduled to be drowned beneath reservoir construction. Guided by their research, John Pfhal photographed the absent presences of these sites. He wanted "to get to those vantage points overlooking the submerged archaeological sites and receive (his) picture."

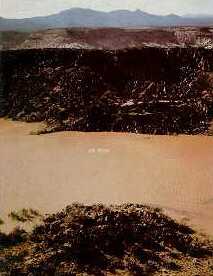

Cochiti Reservoir, "...a masked serpent." The water is like wrinkled brown skin, contrasted against a cap of blue cordillera. The photograph's "deadpan, postcardlike color" (Lippard) relates the understatement of stark juxtapositions that the region can impose on the uninitiated.

What is important to people who live in the mountainous Southwest is gained osmotically over a long period of time. This is, in part, because what is most valuable in this region is "hidden," both objectively and subjectively; so that much of what we anticipated we finally learn to accept based on the faith of imagination. John Pfahl's pictures for this project are a metaphor for this region, transforming sites into venues of psyche as he "focused on the sad patches of water that betrayed not the slightest sign of the profusion of masks, animals, and tiny prints submerged below."

One theme of Marks in Place seems to be preservationist: rock art as cultural treasure. Schaafsma contends that "rock Art is unique in the art world because it is the only artistic artifact from the past that can be seen in its original context," and must does be protected. (In her myoptic anthropologic studies, she misses contemporary environmental art by Smithson, Heizer, Mendieta, et al., already artifacts "from the past.") Ironically, then, the danger of most of the pictures in this book is that they supplement the sites, both adding and replacing. In fact, the Schaafsma's project was pure substitution, as they knew the dams were about to be built. If we follow this through, we can see how pictures of these sites may in turn justify plans to develop them, as their supplements already exist.

Only John Pfhal seems to have recognized this, stamping his pictures with topological reference numbers, and giving them the name of the submerged glyphs. He chose these sites in order to contrive their absence, creating a further presence, a process that theoretically can continue on forever. Just as the ancient artists could not know that they'd be participating in works made hundreds of years later, and by people from a different culture, how can the full extension of our actions and productions be measured?

"A masked serpent" beneath Cochiti Reservoir. "A horned-winged figure" beneath Navajo Reservoir, along with "animals and small hand paints."

An aura seemed to insinuate itself between the perceived sites and our consciousness, so that we became convinced that we had indeed made contact, if only elusively, with the figures themselves and with the ancient Pueblo tribesmen who had crafted them.

The anthropologist claws for sociological clues, structural affinities between the glyphs, in order to classify them. The artist, however, distills a personal taxonomy from the essence of the work, the residue spirit of its maker. For Linda Connor these signs came "slowly and delicately like tiny bubbles materializing and rising to the surface of water put to boil;" while John Pfhal and his assistant "stood above the silty lake trying to make out the approximate location of the small treasures," but were "confronted only with placid swells of opaque water.

6.

Like the other artists represented in this project, Charles Roitz like to speak of essence, and "a sense of place."

In Untitled, British Columbia, Canada, thin fir trees throw a scrim over a forest's floor cambered by roots, littered with fallen branches and scree, sharing growth and decay banking to a small stream. Rocks squat, seemingly spewed out deeply etched with round, gnomic faces.

A wall somewhere in Utah, canvas to complex storyboard of myth: humans coupled with animals, therianthropes along with spirals, meanders, and an overarching rainbow. As it takes a long steep walk to arrive here, Roitz leads us to wonder why these places were chosen. Schaafsma informs us that "painting made during a vision quest by shamans or others desiring the acquisition of power" were made on sites "indicated by their hidden locations to which access may be difficult," as with the Paleolithic caves in France and Spain. Difficult because the vision quest is dangerous, landscape being a putative trace of our real journey?

In Untitled, Washington, 1982, the image of a bear stands among a family of stones. But what seems to interest the photographer is not so much the rock art--in some of his pictures it is hardly apparent--but rather art as one facet of the ecology. His project is to restore, at least in spirit, the original unity of our perception of reality, so that we are no longer conscious of these relations, but experience them haptically.

By reality, or realism, Roitz means "the crawl of a snake, the radiation of a heavenly body. The ancient artist knew how to abstract the essence of form and depict it in these marks," so that the photograph is not a document but a event. As with John Pfhal waiting to "receive" his picture, Roitz wants to "allow the ancient marks and the landscape to imprint themselves on film." In both cases, the artists feel they are stepping out of the way of the marks. Theirs is an practice of permission and trust.

Charles Roitz's venue is the wilderness where, unlike in cities, the ground is uneven and exposed. With each step we must balance differently. detour often, step or climb over countless obstacles that seem to have been purposefully placed in our way, making us feel ingenuous, even clumsy. Orientation here is dedicated to continuous circumstances, in which rocks have their succession, water is alternatively addled, fierce, frozen, or gone, and most animals are transfigured by the seasons. Only humans remain basically the same; adapting instead, or so we tell ourselves.

To the artists of this project, "what finally matters is the rare ability (rock art has) to place us once again in that stream of time where in some undying part of ourselves we are still awake and (seeing), as on the first morning of things" (John Haines), when an anonymous Ancestor reached out and made a purposeful mark.

(c) Joel Weishaus 1988

(c) Artspace 1988