Gary Snyder, Danger

on Peaks

Berkeley: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004.

Joel Weishaus

1.

|

|

|

but under the fiery sign

of Pele, |

At age 15, Gary Snyder climbed to the then 9,677 foot summit of Mt. St. Helens, in southern Washington State. One week before, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first of two atomic bombs on the people of Japan. When the news reached him at his campsite, the would-be poet vowed "something like, 'By the purity and beauty and permanence of Mt. St. Helens," that he would "fight against this cruel destructive power and those who would seek to use it, all my life.'"(9)

In 1980, Loowit, as the Indians call her—"Luwit, lawilayt-lá—Smoky/is her name"(15)—famously erupted, changing her contours and the landscape around her forever. In August 2000, after having published more than eighteen books of poetry and prose, Snyder returned to the mountain, walking in the shadow of her truncated summit, making notes for what would become the first section of Danger on Peaks.

Today, the sound of rain mixing perfectly with the rills of a stream is rubbed raw by a truck grinding up the winding road that skirts Portland’s Japanese Garden. Far off, but within sight of this city, Loowit is again sending up columns of smoke and ash, recreating itself with signs and portents. Taking shelter in a wood-pillared kiosk, sitting on a bench of knotty pine, I begin work on this critique of a book written by a man whose life and work have influenced the better part of mine.

2.

In the summer of 1962, lazing on the sunny beaches of Provincetown, MA, hanging out with artists and jazz musicians at night, before reporting for military service, I was reading two books: Arthur Rimbaud's A Season in Hell; and Donald M Allen's seminal anthology, The New American Poetry, in which some of the major Beat Poets made their national debut. It was here that I first read Gary Snyder's work, a portion of the "Burning" sequence from his second book, Myths & Texts. I had not read poems before that were both erudite and earthy. After reading these poems, I would change my life.

Two years later, I left New York and moved to San Francisco. One morning in the Trieste coffeehouse in North Beach, I was having a long philosophical conversation with the artist Peter Le Blanc. When I mentioned to him that I was applying for a National Endowment for the Arts grant and needed one more reference, Peter said, "How about Gary Snyder?" "Terrific!" I replied. Peter went to the phone booth. When he returned, he handed me Snyder's contact information.

Although he declined to act as a reference, we met many times over the next ten years: in the San Francisco Bay Area, Kyoto, and Kitkitdizze, his homestead outside Nevada City, CA. In 1969, recently returned from Japan with his new family, he was temporarily living in a Japanese-style house in Marin Co. I was living not far away, in the Bolinas home of physician/poet John Doss, and journalist Margot Patterson Doss, where "Ginsberg came half a dozen times and taught me to 'butter steam veggies' one Thanksgiving," while many other poets lived nearby, or visited on weekends. When he invited the household to dinner, that evening Snyder mentioned how at age nineteen he had mapped the path of his career. Coming from a man whose aesthetic is to make a poem as if each word were "placed solid, by hands/In choice of place, set/Before the body of the mind / in space and time," this statement seemed more constrictive than odd. Then I thought of a poem in Myths & Texts:

I sit without thoughts by the log-road

Hatching a new myth

watching waterdogs

the last truck gone.If the myth is large enough, the vision deep enough, the path can accommodate switchbacks and precarious steps.

In 1974, I edited a small book of writing by Sam Thomas, a talented young poet who had taken one of Gary Snyder's workshops at The University of California, Berkeley. On January 8, 1970, "deeply depressed," Thomas had hung himself. Snyder wrote a generous Postnote for the book, remembering, too, his friend Lew Welch who eight months before had "walked off into the woods, leaving behind his sleeping bag, his car, his notebooks, his unfinished MSS, his wallet, his ID. He was never seen again." At the end of that extraordinary decade, living in the high desert of the American Southwest, I attempted to walk away from the influences of my past.

3.

Walk with Snyder's high-minded voice in the shadow of the mountain's devastation, accompanied by geologist Fred Swanson, who's been "studying Mt. St. Helens from the beginning." Snyder explains that after the 1980 eruption, "the Soil Conservation Service wanted to drop $16.5 million worth of grass seed and fertilizer over the whole thing," while "the Forest Service wanted to salvage-log and replant trees," and, of course, "the Army Corps of Engineers wanted to build sediment retention dams." But local activists stopped them, and "zero restoration became the rule."(14) As a result, the natural restoration of the zone became possible. In May 2005, in a talk given by Swanson in Portland, he said that, to everyone's surprise, much of the new growth didn't come from seeds blown in from elsewhere, but from the indigenous burned-over area itself, "blighted by a fall of ash," as Snyder puts it, "but somehow alive."(16).

|

Straddling dichotomies as communal individualism, hospitable ownership, "the pathless path," Snyder's authoritative voice is what wooed Jack Kerouac into making him the hero of The Dharma Bums: an erudite woodsman with an "original mind," as Robert Bly called it, one whose poetry exhibits a "curious combination of smallness and infinity." |

superheated steams and gasses

white-hot crumbling boulders lift and fly in a

burning sky-river wind of

searing lava droplet hail,

huge icebergs in the storm, exploding mud...Discussing how Snyder juxtaposes images in some of this poems, Jody Norton pointed to the shih of T'ang Dynasty

China, which is "a poetry of image rather than idea, in which the images are neither fully drawn nor explicitly located, and in which the precise nature of their interrelationships is not defined." The measured, broken line, "with significant elisions and disjunctions" and "very little enjambment":shoots out flat and rolls a swelling billowing

cloud of rock bits,

crystals, pumice, shards of grass

dead ahead blasting away— (11)While at their best Snyder's poems limn a joyous rhythm, Danger on Peaks opens with pages of prose: the story of Mt. St. Helens' last major eruption, and reminiscences of the mountain when he was young. Lacking the "cicada singing,/swirling in the tangle," in his two major books of prose I found a tedious flat terrain to traverse. Here the writing is more lyrical, comfortably sauntering between poetry and prose, yet still tends to fall into crevasses of figures and facts.

4.

For the past fifty-five years, Gary Snyder has tendered the myth of himself like a plant growing in a wild, though accessible, place. He "re-inhabitated" territory, and recombined aspects of Chinese and Japanese spirituality, knotting it all together with thrums of Amerindian shamanism and lore. His 1969 book, Earth House Hold, introduced to a literary audience the basic concepts of ecology. Coined by German biologist Ernst Haeckel exactly a century before, thanks in part to Snyder "ecology" is now a household word. Its central thesis is the mutual dependency of all living systems and sentient beings, which is also the core teaching of Buddhism, as well as Snyder's poetics.

| "Lookout's Journal" was begun in 1952 when Snyder spent the summer as a fire lookout in the North Cascades of Washington State. It makes up Earth House Hold's first section. Here he was already experimenting with haibun, a combination of prose and haiku which Matsuo Bashō had used to remap the cultural landscape of 17th Century northern Japan. |  |

Witty: ("Ate at the 'parkway café' real lemon in the pie/'—why don't you get a jukebox in here'/'—the man said we weren't important enough'"); profound: ("When the mind is exhausted of images, it invents its own."), Snyder scatted and quoted with humor, and insights befitting an older man. |

Edward Rothstein rhetorically asks, "What artist does not yearn, some day, to possess a 'late style'? A late style would reflect a life of learning, the wisdom that comes from experience, the sadness that comes from wisdom and a mastery of craft that has nothing left to prove. It might recapitulate a life's themes, reflect on questions answered and allude to others beyond understanding." Hermann Broch called this 'the style of old age,' and suggested that it "is not always the product of the years; it is a gift implanted along with his other gifts in the artist, ripening, it may be, with time, often blossoming before its season under the foreshadow of death, or unfolding itself even before the approach of age or death: it is the reaching of a new level of expression..." In particular, the style of old age is "the impoverishment of vocabulary and the enrichment of the syntactical relations of expression."

All this leads us to "Yet Older Matters," the series of short poems that make up the second section of Danger on Peaks—

A rain of black rocks out

of space Crunched

inside yet

older matter

from times before our very sun |

At Elephant Moraine in eastern Antarctica, 160 miles northwest of the United States base at McMurdo Station, nearly 2000 specimens of meteorites have been recovered, including one "as definitely being from Mars;" although, most of the rock fragments, called "chondrites," originated from asteroids. It struck me how, relative to the planet we call Earth, we are all infinitesimally young. Spaced for Snyder's breath/voice,the ma, a gap, "a way of seeing" the interval found between temporal things or events, the poem exemplifies he who "is always a mere breath away from universals."

The balance of this section I find insightfully slight, the poet's personality stronger than the poems. Until the end, at "Sand Ridge," it is as if he suddenly realized that, if our species is to survive, to some extent the path he's traveled we must too, and draws a map:

| Walk

that backbone path ghosts of the pleistocene icefields stretching down and away, both sides |

5.

"Daily Life" is the subject of the third section, poems that read like a journal meant for Literary History. He has always been overtly autobiographical, but the myth now seems somewhat weary. In the first poem, "What to Tell, Still," he is reading "the galley pages of (James) Laughlin's Collected Poems/with an eye to writing a comment./How warmly J. speaks of Pound,/I think back to—" When at twenty-three he sat

in a lookout cabin in gray whipping wind

at the north end of the northern Cascades,

high above rocks and ice, wondering

should I go visit Pound at St. Elizabeths?He went to study Chinese at Berkeley instead, then on to Japan to practice Zen. From, "Working on hosting Ko Un great Korean poet,"(p.43) to the "Summer of '97," when his posse gathered to build his family a new house:

"Sun

for power/Cedar

for siding/Fresh skinned poles for framing/Gravel

for crunching and/Bollingen for bucks—"(p.47) Then

their names and chores are listed: "Daniel peeling/Moth

for singing/Matt for pounding ..."and "Gary

for cold beer." No where did he nail his communal ethics

down tighter than in a 1979 interview with Michael Helm: "No

amount of well-meaning environmental legislation will

halt the biological holocaust without people who live where

they are and work with their neighbors, taking responsibility

for their place, and seeing to it: to be inhabitants,

and not to retreat." |

On the road again, he's "Waiting for a Ride" at the Austin Texas airport(56), or "Heading south down the freeway making the switch/from Business 80 east to the I-5 south,"(50) harking back at least 40 years to "Night Highway 99," in which "Sokei-an met an old man on the banks of the/Columbia growing potatoes & living alone." Sokei-an asks him why he lives there. He replies, in Snyder's voice:

Boy, no one ever asked me the reason why.

I like to be alone.

I am an old man

I have forgotten how to speak human words.One sees that the footloose young poet dreaming of adventures to come. Then the middle-aged father "on my way to pick up my ten-year-old stepdaughter/and drive the car pool."(p.41) Stages of a life, accepting this, he will stick to human words. How to go on? "Steady, They Say," which is the book's fourth section.

There's a poem that I first read in a magazine's tribute to poet/Zen Master Philip Whalen, Snyder's roomie at Reed College and lifelong friend. When I moved into the Bolinas house of John and Margot Doss, it was because Whalen, who had lived there, had left for Japan. In the bedroom's dresser I found a large-sized pair of underwear, and holey tabi, Japanese split-toe socks. Danger on Peaks has two poems dedicated to Whalen, who, blind and enlightened, died on June 26, 2002. Seeing this one, "Claws / Cause," collected here is what made me buy the book.

"Graph" is the claw-curve, carve—

grammar a weavingIn the thrust of a complex text, too many critics twist its guts, as if one can breath life into death. I could speak to "the veins in stones and wood, to constellations, represented by the strokes connecting the stars, to the tracks of birds and quadrupeds on the ground (Chinese tradition would have it that the observation of these tracks suggested the invention of writing)," but creativity is raw energy: the reader must be moved. Thus, the claw of an extinct animal was curved to carve flesh, or dig for roots, and us. Then, in the art of weaving we uncovered a grammar like the Navajo spirit road, working its way through like a "paw track, lizard-slither, tumble of/a single boulder down," over the edge. A poem accepts its death like a sentence its period. A poem is its own eulogy, "Saying, 'this was me'/scat sign of time and mood and place," and "language is breath, claw, or tongue." From between the lips, what darts out, or draws in.

Youth may blossom unexpectedly, this poem, reminiscent of one Snyder wrote more than 35 years ago, which ended simply: "Eating each other's seed/eating/ah, each other./Kissing the lover in the mouth of bread:/lip to lip." Now, "'tongue' with all its flickers/might be a word for

hot love, and fate.

A single kiss a tiny cause [claws]A whispered word quivers like a kiss blown across a room, bridging streams of meaning to make

– such grand effects [text].

More personal poems: To his wife, whose legs were trained "by the/danger on peaks,"(74) to his Japanese mother-in-law, "needing no poem,"(66) and "To All the Girls Whose Ears I Pierced Back Then."(64) He travels from the Mibu River, "Four hours from Tokyo."(83) back to the Yuba River, "where it enters the Sacramento valley flatlands,"(85) to "the soaring Parthenon, sacred to gray-eyed Athena." Bivouacking there, he "Dreamed of a gray-eyed girl/on this rocky hill/no buildings/then."(88)There's also a haibun for his sister, Anthea, who was "struck by a speedy car, an instant death."

White egrets standing there

always standing there

there at the crossingon the Petaluma River.(96)

All paths lead to the mystery of one's existence; yet we love the material arts, the liturgical words, the robes of spiritual office, an incense burner's perfumed clouds. I reached Rytakuji in the autumn of 1968. A Zen monastery built in the 18th Century in view of Mt. Fuji, its peaceful ambience, national treasures, and brilliant abbot, Soen Nakagawa, moved me to write to Snyder, who was in Kyoto preparing to leave for America, something like, "Now that I've found Paradise, what do I do with it?" He replied, "Beware of the fox inside." Japanese trickster, who in the Western USA is Coyote, would "say 'that's just what I thought too'/And do it. And go his way."(59)

6.

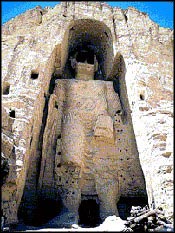

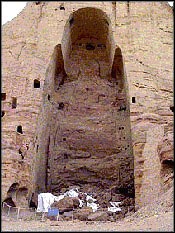

In Kyoto, "the great bell of Gion/one hundred eight times/deeply booms through town."(97), while through my open windows today, a church bell's deep throat opens twelve times, unwittingly tolling the destruction of Bamiyan.

On November 13, 2001, the BBC News reported that Islamic fundamentalists had dynamited the giant Buddhist sculptures that were carved into the Hindu Kush mountains of Afghanistan, "claiming that all statues were false idols and contrary to their Islamic beliefs." First mentioned in 5th Century A.D. by the Chinese traveler, Fa-hsien, 200 years later, the Buddhist pilgrim monk, Hsüan-tsang, saw the figures decorated with jewels and gold. In Mountains and Rivers Without End, Snyder included the lovely lyrical poem, "The Hump-backed Flute Player." First published in 1971, with a flawed finish he later rewrote but still rings false, the poem begins in Canyon de Chelly, where, "on the south wall, the pecked-out pictures of some mountain sheep with curling horns," join a humpbacked flute-player, a solitary and mysterious flute-playing creature known to the Hopi as Kokopelli, who "may have been as important to the Southwestern Indians as Abraham is to Jews or Paul to Christians." To Snyder, Kokopelli's "hump is a pack," which he associates with Hsüan-tsang, who walked to India and returned to China sixteen years later with the Buddhist teachings of emptiness, of "mind-only," vijñaptimātra.

In the last section of Danger on Peaks, Hsüan-tsang appears again, as Snyder laments the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan "by woman-and-nature-denying authoritarian worldviews that go back much farther than Abraham."(101) "And yet," he replies to a letter "from a man who writes about Buddhism," "'and yet' is our perennial practice. And maybe the root of the Dharma."(102) A stubbornly compassionate vision—"walking the pilgrim path,/climbing the steps to/Avalokiteshava, Bodhisattva of Compassion/asking: please guide us through samsara"(105-6)—in midst of Gaia and her children being sacrificed to Power & Greed. "What was that?/storms of flying glass/& billowing flames...better than burning, hold hands.(104)

Backpacked into this century by tens of thousands of readers, Gary Snyder remains a unique presence. As exemplar of a sustainable planet, his is a life lived large and, more often than not,writ brilliantly—

For all beings

living or not, beings or not,inside or outside of time (106)

References

1.

The white dome peak: G. Snyder. From, "The white dome peak..."

2.

the artist Peter LeBlanc: "In early morning, during spacious coffee-breaks, we would sit in the empty saloon and talk about the nature of our creative drives and aspirations. Our conversations were intense but not without humor. We were both convinced that we were absolutely right, no matter what, as long as we remained true to our work." D. Meltzer, "Beat Generation Poets: The Prints of Peter Le Blanc." Bastard Angel, Fall 1974. p.2.

Ginsberg came: M.P. Doss, "A Reminiscence of #9 Brighton." Bolinas, CA, 1998.

placed solid / by hands: G. Snyder. From, "Riprap." In, Riprap & Cold Mountain Poems. San Francisco, 1969. p.30.

I sit without thoughts: G. Snyder. From, "First Shaman Song."

I edited a small book: Bits & Snatches: The Selected Work of Sam Thomas. Introduction by Dr. D.H. Rosen & Postnote by Gary Snyder. Brooklyn, NY, 1974.3.

a curious combination: C. Altieri, "Gary Snyder's Lyric Poetry: Dialectic as Ecology." In, P.D. Murphy, Critical Essays on Gary Snyder. Boston, MA., 1991.

the pathless path: When Yaoshan Weiyan visited Shitou Xiqian and asked him about the teaching of the Southern School of Ch'an Buddhism, Shitou replied, "This way will not do, nor will any other way do. Neither this way nor any way will do. What do you do?" Contemporary Zen Master, Shin'ichi Hisamutsu, echoed this with, "Nothing will do. What do you do? Snyder replied with, "Knowing nothing need be done / is where we begin from."

a poetry of image: "The Importance of Nothing: Absence and Its Origins in the Poetry of Gary Snyder. In, P.D. Murphy, Editor, Critical Essays on Gary Snyder. Boston, MA, 1991.

cicada singing: G. Snyder. From, "Song of the Tangle." In, Regarding Wave. New York, 1970.

two major books: The Practice of the Wild: Essays. San Francisco, CA, 1990; A Place in Space, Washington, D.C. , 1995.4.

Earth House Hold: New York, 1968.

Edward Rothstein: “Twilight of his Idols.” Review of Edward W. Said's, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain. The New York Times, 16 July 2006.

Hermann Broch: "The Style of the Mythological Age." Introduction to R. Bespaloff, On the Iliad. Washington, D.C., 1947.

as definitely being from Mars: Astrobiology Magazine, 7, November 2002. http://www.astrobio.net/news/print.php?sid=308

the ma, a gap: See, R.B.Pilgrim, "Intervals (Ma) in Space and Time: Foundations for a Religio-Aesthetic Paradigm in Japan." History of Religions #3, February 1986. Snyder also wrote poem titled Mā (In, Mountains and Rivers without End. Washington, D.C., 1996."Snyder has said that 'Mā' is an actual letter he discovered in an abandoned shack in the mountains not far from his home on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. " A. Hunt, Genesis, Structure, and Meaning in Gary Snyder's Mountains and Rivers Without End. Reno NV, 2004.

is always a mere breath: R. Peters, review of Axe Handles. San Francisco, CA, 1983. Sulfur #10 1984.5.

Working on hosting: "Widely acknowledged as Korea's foremost and most prolific living contemporary poet, Ko Un is finally becoming known and recognized outside of Korea as more translation of his 130 diverse books–volumes of poetry (from short lyrics to sweeping epics), fiction, essays, translations and drama–become available in major Asian and European languages." "Ko Un: Human Nature Itself is Poetic." Interview by P. Donegan. Kyoto Journal 60, 2005.

No amount of well-meaning: In, W.S.McLean, Editor, The Real Work: Interviews & Talks 1964-1979. p.161.

Night Highway 99: In, Mountains and Rivers Without End. Washington D.C., 1997.

in a magazine's tribute: Shambhala Sun, November 2002. G. Snyder, "Highest and Driest."

the veins in stones: J. Gernet, quoted in J. Derrida, Of Grammatology. Baltimore, MD, 1976.

Eating each other's seed: From, "Song of the Taste." In, Regarding Wave. New York, 1970.6

may have been as important: J.W. Sharp, "On the Trail of Kokopelli." http://www.desertusa.com/mag00/ apr/stories/trail_kok.html