POETICA

Critiques

of Poetry and Poetics

Joel Weishaus

Margaret Chula, Just This.

Mountains & Rivers Press: Eugene, OR, 2013.

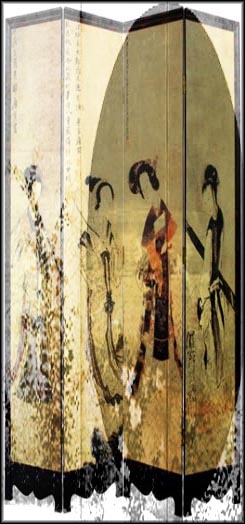

1."The dexterity of the brush, the style of composition, the fold, texture, and pattern of paper significantly marked the courtier's position in relation to others. Diaries and tales turned around poems; lovers navigated through trysts and alliances and poems; poems punctuated the rites and ceremonies that negotiated the cosmological dimension of court bureaucracies; and poems flowed with major and minor exchanges of wealth."1

One can only fantasize what a modern society in which "poetics permeated all aspects of life," including its political and economic life, would be like. Language would not be jockeyed around, but carefully tended. Thoughtful writing and speech, instead of 24-hour electronic blather, would be honored. Perhaps even romantic love would flourish again. This was actually the case during Japan's Heian Period (794 to 1185), at least in the lives of the Heian Court's privileged class.

Looking closer. The female role in the Heian Court was complicated by what Thomas Lararre refers to as the "sexed gait," in which the noble woman of Heian Japan were hobbled "with layers or robes and dresses that "lower(ed) the center of gravity and raise(ed) the center of motion to such an extent that movement produces a wobbling, toppling, swaying, or swooning effect."(1) Lamarre compares this movement to "the dynamics of early Heian waka," the popular "song poems."

Critiquing the famous Heian poet, Ono no Komachi, poet and anthologist Ki no Tsurayuki's (872-945) associated "the Komachi style with female weakness, like that of a noble woman who writhes in bed, devastated with illness and suffering. The poetic line turns and pivots too much for Tsyrayuki: it fairly writhes and collapses." "Indeed," Lamarre continues, "that is often said to be the hallmark of her poetry: a multiplication of pivotwords to the point of vertigo and collapse."1

Lamarre's point is how restricted movement of the body shapes one's writing. He primarily has in mind how the hand brushes out characters. But it also includes the sense-shape of the poem itself; the poetic form being waka, the thirty-one syllable poem that, although it's had ups and downs in popularity, has survived for twelve centuries.

2.

Around the turn of the 20th Century, Western experimental literary forms began to arrive in Japan, brought back, in part, by Japanese writers who had lived for a time in Paris. As the Japanese have always been expert at innovating the ideas, and technologies, of other cultures, a group of young "socialistic" poets took up the challenge of transforming the staid waka form into a more modern idiom, renamed tanka, or "short form." Around this same time, Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) was transforming the seventeen syllable hokku format into modern haiku. Among these poets was the gifted Ishikawa Takuboku, (1886-1912) whose died prematurely from tuberculosis. Takuboku famously defined tanka as "poems made with both feet upon the ground.

It means poems written without putting any distance from actual life. They are not delicacies, or dainty dishes, but food indispensable for us in our daily meal. To define poetry in this way may be to pull it down from its established position, but to me it means to make poetry, which has added nothing or detracted nothing from actual life, into something which cannot be dispensed with."2

Although both waka and tanka are somewhat interchangeable, tanka is usually used to define poems written after the turn-of-the-century reforms. They usually (although not always) begin from an objective viewpoint, the poet placing herself in the world, and then turn thoughtfully, or imaginatively, inward. Traditionally, the first three lines are called kami-no-ku, or, "upper phrase," and the last two, shimo-no-ku, or "lower phrase." The middle line may act as a hinge, or pivot, indicated with a dash or a space. Punctuation is kept to a minimum; or, as in the case of Chula's tanka, there's none at all. Like with haiku, the original Japanese was scribed in a single line.

3.

In 1990, Jane Hirshfield and Mariko Aratani translated a collection of love poems by Ono no Komachi and Izumi Shikibu. (2) In their introduction they state how Chinese was the official court language, with written Japanese, "using Chinese characters phonetically to transcribe spoken Japanese," began being accepted at the end of the 8th Century. Unburdened as male writers were from the "need to satisfy the requirements of foreign poetic structures and sensibilities,

women could devote themselves to developing their literary potential to the highest degrees in the poems, diaries, and 'tales' in which they recorded both public and the most private and deeply felt aspects of their lives."3

Their emphasis is on women "striving to bring (the arts) to everyday communication," was limited to whom we now call "the 1%," as the general populace was either illiterate or too busy trying to survive to participate in the arts that were being made at court. They explain that, for high-ranking members of the Heian court, "love affairs were an accepted part of courtship for unmarried women, and polygamy was the usual arrangement for men. Thus, erotic love and its consequences were perennial conversational and literary topics. Within this atmosphere, Ono no Komachi "became the subject of legend almost from the time of her death," and some of her waka, which remind me of Sappho's fragments, are among the best erotic poems to come down to us from antiquity. Such as:

Lying alone,

my black hair tangled,

uncombed,

I long for the one

who touched it first.Izumi Shikiku, married for a time to a provincial official, the mother of a daughter who herself would become a poet, was involved in numerous passionate affairs with court officials. Under the protection of the father of Empress Akiko, she moved within the company of some of the most famous Japanese woman writers, such as Murasaki Shikibu (Lady Murasaki), author of The Tale of Genji, and Sei Shōnagon, author of The Pillow Book. An example of Shikibu's waka is:

What is it

about this twilight hour?

Even the sound

of a barely perceptible breeze

pierces the heart.Both Shikibu's and Komachi's waka, translated by Hirshfield and Aratani, introduce sections of Just This, Margaret Chula's recent collection of tanka.

4.

In 1977, Margaret Chula and her husband began a three-year trek through Europe, Bali, Borneo, Nepal and Southeast Asia, finally arriving in Kyoto, where she taught English for the next twelve years. While her husband became a student of the martial arts, Margaret studied ikebana (flower arrangement), practiced meditation with a Soto Zen priest, and spent "many hours at Ryoan-ji and other temples sitting and writing haiku, affirming the Japanese saying zenshi ichimi, zen and poetry are one." 4

When the couple returned to the U.S. they made their home in Portland, OR, where, in 1992, Chula published her first collection of haiku, Grinding My Ink, which won that that year's Haiku Society of America Merit Book Award. Here's the title poem:

grinding my ink

a black cat

howls in childbirthIn the sudden leap, the way an ominous color permeates the poem, and in her move from material act to emotive moment, one can begin to see Chula's emerging gift.

For Just This, her seventh book, Chula chose the five-line tanka. Dedicated to her mother, who died the year before the book was published. the first poem, which is one the most beautifully wrought and poignant of the book, I assume was written with her mother in mind—

late summer

in the garden

just before dusk

touching leaves and flowers

as I never touched youSo she begins with an ending. As the book's epigram says, "it is the beginnings and endings that are interesting and what seems simple on the surface is actually a picture of the complex relationships." (5) This is followed by a beautifully said mundane poem—

again distracted

while making breakfast

my husband's angry face

as he spreads marmalade

on burnt toastEspecially in the haiku or tanka form, the best poems may at first read seem simple. If we a closer look, we may see how a master of the medium, such as Chula, works. Here, the poem leaps out on the third line, hinging on a kabuki mask of anger. Then the tension is release with humor, as, at time such as this, a good marriage demands some stoic sacrifice. In fact, there is a tradition of "comic waka" (kyōka).

As mentioned above, waka/tanka stems from erotic poems, which can be associated with a metaphoric earthiness. Here, Chula combines both—

a spring day spent

turning the garden soil

to my heart's content

tonight I will caress you

with these earth-bound handsAlthough she's traveled, and continues to travel widely, and so has experienced, and studied,many cultures, Margaret Chula's heart is centered in the arts, literature and spirituality of Japan. Like with other American poets who are drawn to East Asian cultures, in particular those who live near the Pacific Northwest Coast, this could be cultural proximity. Or, if one believes in past lives, karma, or moria, the attraction would understandable. I prefer mysterious causation. In any case, when such an art as tanka is practiced by someone with the alert intelligence of this poet, the effect is an aesthetic beauty and refined sensibility that permeate this book.

those half-empty jars

of her cosmetics

why did I keep them?

rubbing in face cream

I feel my mother's bones

References:

1- Lamarre, T. (2000) Uncovering Heian Japan: An Archaeology of Sensation and inscription. Durham.

2- Ishikawa, T. (1985) Romaji Diary and Sad Toys. Boston.

3- Hershfield, J and Aratani, M, (1988) Eds., The Ink Dark Moon. New York.

4- Chula, Margaret, "Personal Essay."

5: Yoshida, Kenko (1283-1352).