At

what is now Independence Fiord, in the extreme High Arctic, cut

off from the rest of the world by "the great ice wall," Paleo-Eskimos,

hunted muskoxen, cooked over open fires, gathered birds' eggs during

the short summers, hunted hares, and fished from the shore. They

had lost their knowledge of the bow and arrow, of the kayak and

sea-going vessels. But with the gods and spirits they found there,

they were able to start over again.

"the

practices and beliefs of the shaman posed a model of behavior

for others to potentially utilize in times of personal distress.

Dissociating one's anxious mind into the realm of the supernatural

is a familiar human mechanism for handling problems unsolvable

by other means."

"Pindlingayak

means a fool, and Pindlerortok a mad or delerious person.

By degrees, as madness increases, disturbing the operation of

the senses and clouding the judgement and insight into things

present, the absent or concealed things and the events of the

future unfold themselves to the inner sight of the insane."

H.

Rink, Tales and Traditions of the Eskimos. Edinburgh, 1875.

This

morning I thought about giving away the backpack I’ve had

for over thirty years. In the mid-1970s, it carried supplies

up the mountain to my California hermitage. In the early 1980s,

it swayed to the rhythm of the steep trail into New Mexico's

Sangre de Cristo Mountains. So much sweat on the brow and running

down the back! So many pounding heartbeats as the

importance of magico-religious beliefs and their association

with Dorest technology is apparent in the most striking accomplishment

of the Dorset people: the creation of a body of art that is unique,

unexpected, and it struggled to keep pace. Now

my backpack carries only memories, "the

odd otherness of things."

Fearing

a runner, a dog, or a person looking up, would crush them, on

a twig I carried two parts of a worm, both wiggling, to the side

of the trail, where

a small purple flower clung to the cold earth.

a small purple flower clung to the cold earth.

R.

McGhee, Ancient People of the Arctic. Vancouver, B.C., 1996

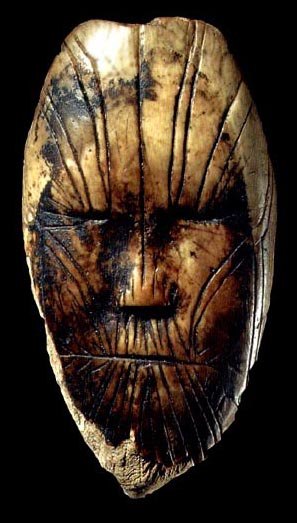

Ivory

maskette 3,500+ years old, is the oldest known Paleo-

Eskimo portrait of a human.

Eskimo portrait of a human.

E.F.

Foulks, The Arctic Hysterias. Anthropological Studies #10

(1972)

D.

Abram. From an address given to the "Nature and Human Nature

Conference, " Pacifica Graduate Institute, Santa Barbara, CA.

March 2007