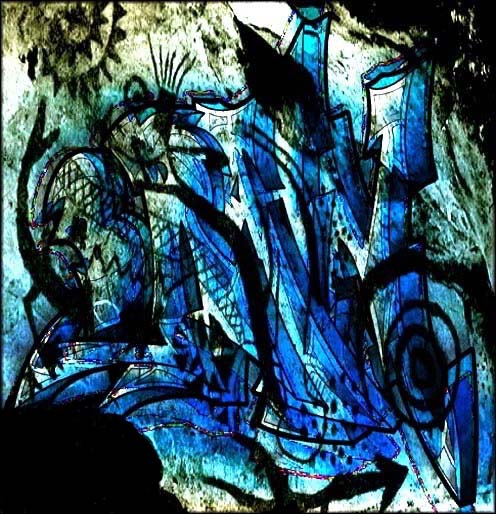

In our expanding view of art history, a continuum can be seen from Paleolithic cave art to contemporary Graffiti Art. Also called "urban hidden literature," it is not readily recognized as literary (or, in some sectors, art) because the complexity of its designs lifts itself from graphic novels and Japanese manga, not traditional print.

In Graffiti Art the alphabet itself is the sign. Perhaps, unconsciously, it is a magic language, like the Hebrew Kabbalah. Or compare it with Heian calligraphy, which "delivers signs from other realms through the human body, or rather through its heart/mind...unfurl(ing) lines that the eye often can barely follow."

Controlling pressurized cans to lay up "a loud and colorful voice," is akin to a painter learning brush technique. It also traces to the Paleolithic caves, where

"the evidence indicated that the ancient artists were blowing the pigment out of their tubes with a pressure of about 40 pounds per square inch, which is equal to a modern pressurized air-brush system."

In no other Western art are words and images so successfully combined. For the artist, it's "a beautiful crime." For people whose walls have been painted without permission, it is just a crime. Where "someone built a campfire near the so-called First Panel, then used charcoal to scrawl graffiti on some of the ancient Native American rock art," there is neither literature nor art.

Archaeologist

David S. Whitley wrote, "Rock art is landscape art." Graffiti

artist,

Mear, said that, "Graffiti artists are reflecting their

surroundings." Perhaps the

landscape can guide us to see the difference between desecration and

belief.